Tracking Parasites

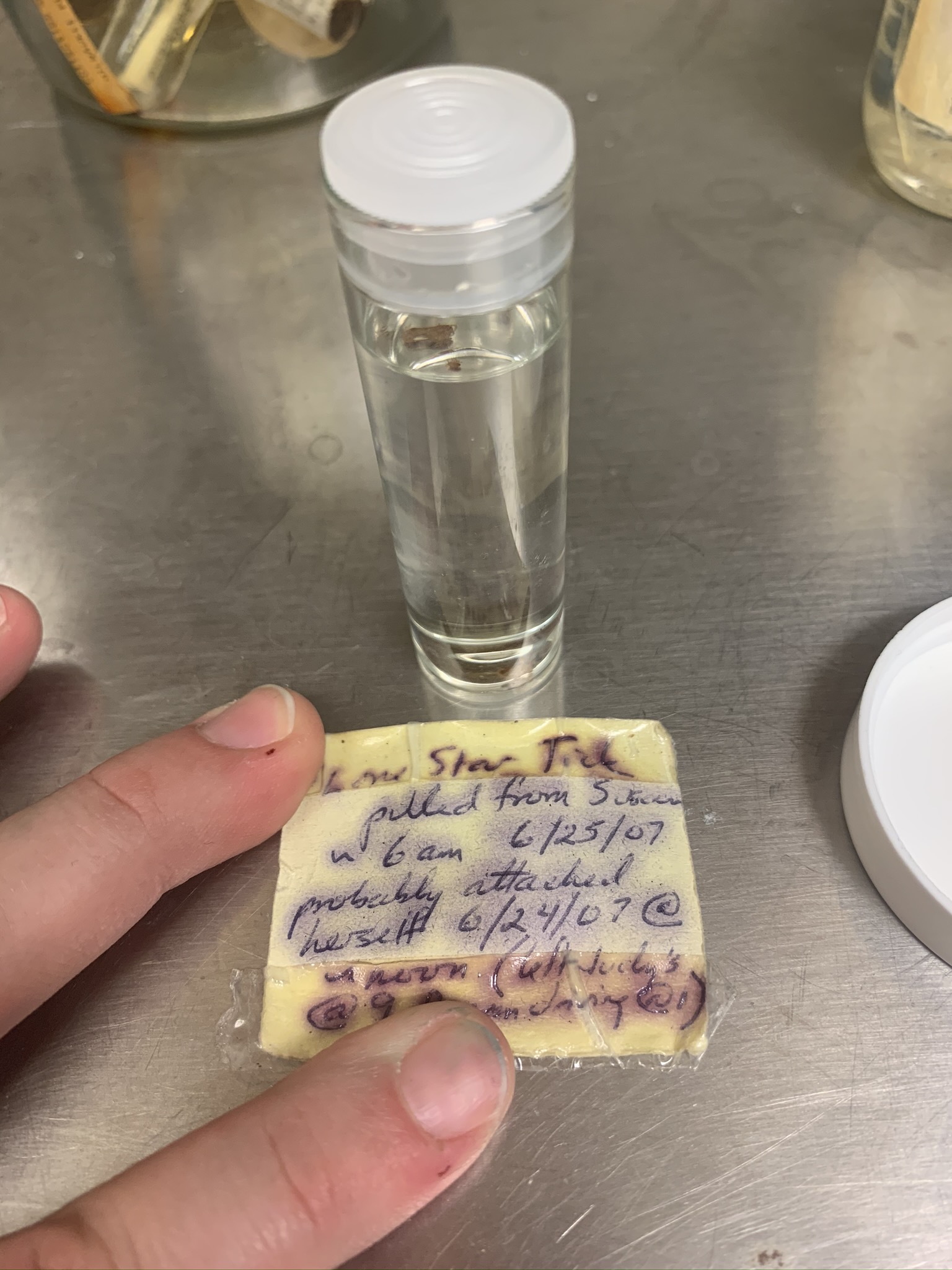

Figure 1. A parasite specimen and associated label from the Milwaukee Public Museum Invertebrate Zoology Collection (MPM-IZ) that was used in the group transcription exercise during the Terrestrial Parasite Tracker workshop on February 24-25, 2020 in the Field Museum, Chicago, IL. (A more specific specimen citation is pending as the specimen is still being processed)

After months of preparations, about fifty contributors to the NSF-sponsored (DBI:1901926, DBI:1901932) Terrestrial Parasite Tracker (TPT, https://parasitetracker.org, [1]) Thematic Collection Network gathered in the Field Museum in Chicago, IL for a workshop on February 24-25, 2020. The goals of the TPT workshop were to share ideas on how best to digitize parasitic arthropod specimens and make their associated digital records easily and openly accessible in order to build a better picture of how these little creatures (e.g., ticks, lice, mites) spread diseases and parasitize their hosts. The TPT project uses GloBI to find, index and review parasite-host associations captured in openly accessible digital collections shared by participating institutions.

Physical specimens in natural history collections are often accompanied with handwritten or printed labels (fig. 1). For parasite specimens, these labels often contain valuable information about the environment or organism from which they were collected. This information carries clues about what hosts these parasites may associate with. One highlight of the workshop was a transcription exercise: workshop participants were put into eight groups and were tasked first to individually transcribe (fig. 2) enlarged prints of specimen labels using a provided datasheet. Then, each of the groups discussed their transcription results and attempted to reach consensus on how to transcribe each of the provided photographed labels. After that, each of the groups presented their results and discussion followed. The main takeaways from the transcription results and lively discussions were that (a) labels should be transcribed verbatim and (b) interpretation of the verbatim terms should be done by experts using well-defined terms. So, when a label says, “pulled from Susan,” the transcription should say “pulled from Susan.” However, an interpretation of the transcription may say, “associated with: Homo sapiens,” or perhaps even “has host: Homo sapiens.” The group discussions made it clear that multiple interpretations of a single specimen label may exist. Some of these interpretations, or subjective claims, may even contradict each other.

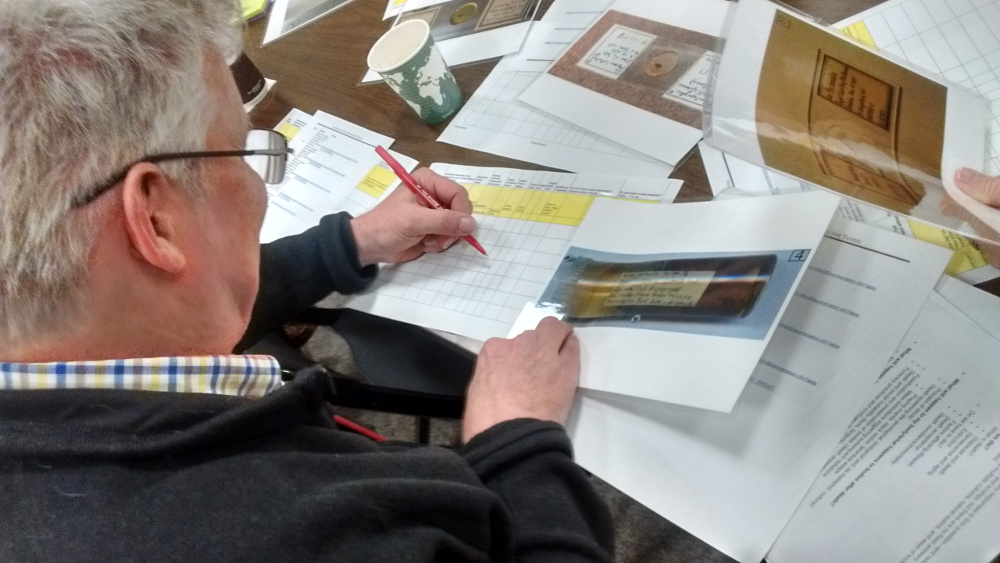

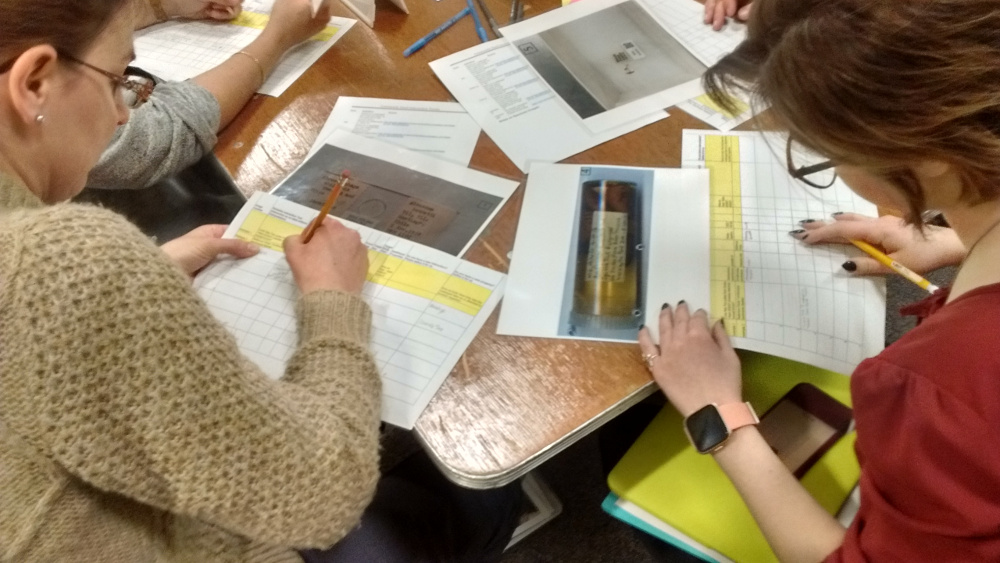

Figure 2. Terrestrial Parasite Tracker workshop participants transcribing specimen labels as part of a group exercise on February 24, 2020 at the Field Museum, Chicago, IL.

To help keep track of the digitization efforts, a data paper was published [2] and a dedicated TPT web page was created at https://globalbioticinteractions.org/parasitetracker (see also [3]). The data paper contains a citable snapshot of the project, while the web page contains up-to-date information about TPT-affiliated collections and their associated data reviews, indexed interactions and data workflows (i.e., integration profiles). Also, the web page contains various examples of how to use Darwin Core archives to capture biotic association data. In addition, some pointers to biotic interaction term definitions are listed on the page as well as translation tables that detail how association terms provided by the collections (e.g.,”on:”, “ex:”) are interpreted by GloBI.

As the mutualistic partnership between TPT and GloBI matures in the years to come, the TPT-affiliated collections and GloBI will coevolve to improve access to, and use of, physical specimens of vectors and parasites in research, education, policy and management.

References

[1] Purdue University. (2019, August 13). Purdue leading effort to digitize North American parasite collections [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.purdue.edu/newsroom/releases/2019/Q3/purdue-leading-effort-to-digitize-north-american-parasite-collections.html

[2] Poelen, Jorrit H., Seltmann, Katja C., & Campbell, Mariel. (2020). Terrestrial Parasite Tracker indexed biotic interactions and review summary (Version 0.1) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3685365

[3] Poelen, J. H. (2020, February 27). Global Biotic Interactions: On Keeping Track of Parasite-Host Specimen Records. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/VK8WQ